Gerald Dixon – On a wing and a prayer.

Second Lieutenant: RFC in World War 1.

Squadron Leader: RAF in World War 2.

Being asked to fly Gerald in the year of his 100th birthday was both an honour and a privilege. It was 1999, and Gerald, despite his age, was a remarkably spry and jovial character. With his sharp wit and infectious spirit, he was an absolute delight to be around.

The aircraft was a Tiger Moth a type he had spent countless hours in during the Second World War. As he took the controls, it became clear that the passage of decades had not dimmed his skill. Gerald’s steady hand and instinctive touch were a testament to his enduring connection with the skies.

The experience was a beautiful reminder of resilience, passion, and the timeless bond between a pilot and their craft.

Gerald Dixon spent his retirement in a charming house on Marine Parade, West Worthing. Sussex. Born at the very end of Queen Victoria’s reign, Gerald often reflected on how his generation had witnessed more dramatic changes in the world than any before—or perhaps since. Some may debate this claim, but his life experiences stand as a testament to an extraordinary era of transformation.

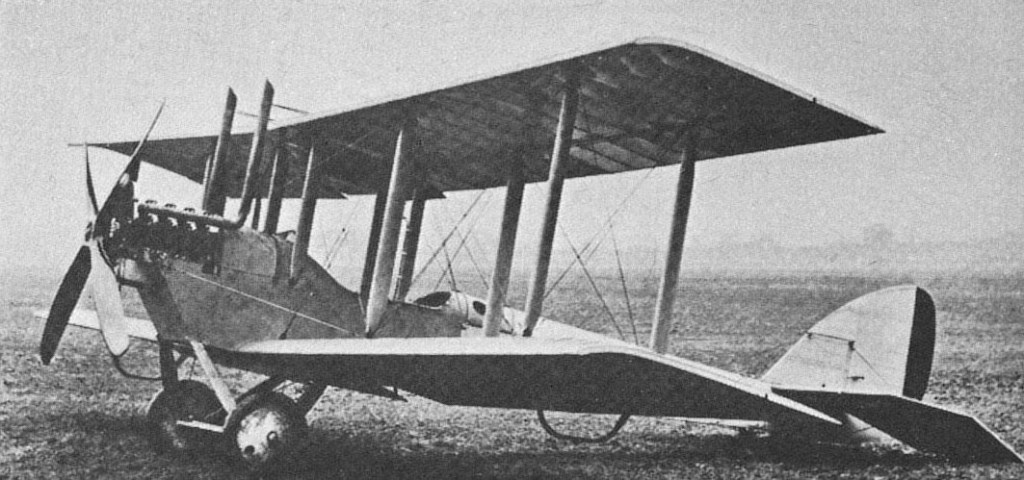

In recounting Gerald’s journey, I must give credit to the late ‘Freddie Feest’ and my friend ‘Alan Fowler’ from RAFA Airshow days. This piece vividly recalls the remarkable advancements in aviation, particularly during the early “stringbag types of aircraft” in World War One. Gerald was there, captivated by the early days of flight, and dreaming of becoming a pilot in what many optimistically called “the war to end all wars.”

Gerald Dixon: A Century of Flight

Gerald Dixon was born on September 6th, 1899, in the heart of Lancashire, as the world teetered on the brink of the 20th century. His arrival coincided with the outbreak of the Boer War, a tumultuous time that would, ironically, mirror the challenges and triumphs of his own life.

During the jubilation surrounding the relief of Mafeking in 1900, a young Gerald made an inauspicious debut into adventure. He tumbled out of his pram during the street celebrations, hitting his head—a mishap that would mark the beginning of a challenging path. School reports later described him as a “slow learner,” a label that followed him throughout his education.

At age six, another obstacle arose: Gerald contracted tuberculosis, a grave diagnosis at the time. The illness interrupted his early schooling and cast a shadow over his formative years. Yet, he proved remarkably resilient. When his health permitted, Gerald attended Bedford College, where his passion for sports and games brought him fleeting moments of normality and joy.

It was during a family holiday that young Gerald’s destiny took shape. Watching the famed Gustav Hamel, a pioneering aviator, land his aircraft in a nearby field sparked an indelible dream. Hamel’s display of daring ignited a passion in Gerald that no obstacle could extinguish. He longed to soar above the constraints of earth and circumstance.

Eager to pursue his dream, Gerald approached life with a singular focus. Despite his struggles with academia, he was determined to chart a course to the skies. On his 18th birthday, September 6th, 1917, he presented himself at the Royal Flying Corps headquarters. With the Great War raging, Gerald was ready to trade his ground-bound existence for the freedom of the open skies.

Gerald Dixon: A Skyman’s Journey

With his dream of flying finally within reach, Gerald Dixon joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in 1917.

From an interview by the late ‘Freddie Feest’ for http://www.worthinghistory.com

The Making of a Royal Flying Corps Cadet: Gerald Dixon’s Journey

In the heady early days of the First World War, when patriotism surged and promises of a quick resolution loomed, schoolmasters and students alike rushed to enlist. Many of those schoolmasters would never return, their hopes dashed on the battlefields. By September 1917, the war was far from over, and Gerald Dixon found himself at London’s grand Hotel Cecil, where he joined the ranks of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) as a cadet.

From there, he embarked on a journey that would forever define him, filled with both challenges and the heady excitement of being part of something groundbreaking.

The Hardships of Halton and Hastings

Geralds first stop was Halton, near Wendover, where he and his fellow cadets were promised their full kits upon arrival. Reality, however, told a different story. It took ten long days before they received even the most basic cutlery for meals. Yet, the youthful enthusiasm of the group never wavered, and not a single complaint was heard.

Life at Halton wasn’t without its trials. Heavy inoculation doses left the cadets ill, a harsh introduction to military life. From there, they moved to Hastings, where the drill sergeants introduced them to a new and “harsh language” that Gerald, even years later, deemed unnecessary. Still, by the end of their training in Hastings, they had become a smart and disciplined unit—a tradition of excellence that persists in the Royal Air Force to this day.

Learning (and Surviving) the Art of Flight

Gerald’s first solo flight was in a De Havilland DH6, an aircraft affectionately nicknamed the “clutching hand” for its less-than-stellar handling. Reflecting on his early flying days, Dixon remarked:

“We learned to fly, but no way were we taught.”

In an era when aviation was still proving itself, Field Marshal Haig clung to cavalry, and admirals scoffed at the idea of aircraft threatening battleships. The RFC cadets faced immense challenges, including the staggering statistic that 8,000 pilots were killed in training—more than those lost in combat over the Western Front.

After his initial flight experience, Gerald moved to Oxford to study airframes, engines, and Morse code. Of the engine instructors, he wryly noted:

“Any hole in an engine was always explained away as being either for lubrication or lightness!”

From Oxford, he went on to Uxbridge, where he was part of the first course to study machine guns—a necessary skill, given the dual demands of flying temperamental aircraft and handling frequent gun stoppages.

Catterick: The Final Test

Gerald’s most thrilling posting was to Catterick in Yorkshire, where he truly learned to fly. He spoke of this time with deep respect:

“I use the phrase again ‘learning to fly’ with great feeling, for in no way were we ‘taught to fly.’”

The skies over Catterick bore witness to the bravery and determination of young men like Gerald, who faced the dangers of early aviation with courage.

Posted to Saint- Emaire in France, he was thrust into the perilous world of aerial warfare. Flying DH4s, DH6s, and DH9s, Gerald carried out bombing raids over Mannerheim, targeting railways and viaducts vital to enemy supply lines.

Life as a bomber pilot was fraught with danger. The RFC’s casualty rates were staggering, and the average life expectancy of a bomber pilot was a mere four weeks. Gerald, however, seemed to possess a blend of skill, determination, and perhaps a touch of luck. As the war ground on, the Armistice of November 1918 arrived in time to spare him from the fate that had claimed so many of his comrades.

The war also marked a pivotal moment in aviation history. On April 1, 1918, the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service merged to form the Royal Air Force (RAF), the world’s first independent air force. Gerald was part of this historic transformation, though peace soon brought downsizing. By 1919, the RAF was reduced from over 200 squadrons to just a dozen. Gerald, holding the rank of Second Lieutenant, was demobilized that same year.

Returning home to London, Gerald found a changed world. His father had passed away during the war, leaving his widowed mother to care for Gerald’s younger brother. Stepping into his new civilian life, Gerald explored various jobs before discovering his calling in hospitality. Partnering with a colleague, he ventured into the hotel business, carving out a successful career as a hotelier in southern England.

Gerald’s postwar years were a testament to resilience and reinvention. Though he had left the skies behind, his wartime experiences and his determination to succeed grounded him in a new life.

Gerald Dixon: A Life in Service and the Sky

As the world braced for the outbreak of the Second World War, Gerald Dixon once again answered the call to serve. By this time, he had married his first wife, Pat, and sold his share of the hotel business to his partner. With his aviation skills and experience still sharp, he rejoined the RAF. Though too old for operational flying, Gerald was appointed Chief Instructor at Halton Park.

Promoted to the rank of Squadron Leader, Gerald played a crucial role in shaping the RAF’s future. Under his guidance, thousands of cadets were trained as pilots, navigators, and air gunners. His dedication to the war effort ensured that his legacy would endure through the success of those he mentored.

Decades later, Gerald’s contributions to the RAF were formally recognized at the celebration of the 75th Anniversary of its formation. There, he had the honor of meeting both the Queen and the Queen Mother. Ever the steadfast serviceman, Gerald stood to attention when addressed by the Queen. Despite her gracious suggestion that he sit down, Gerald politely but firmly remained standing. It was, as he would later recount, the only order he had ever disobeyed.

In 1999, at the remarkable age of 100, Gerald experienced a fitting tribute to his love of flying: a flight with me in a Tiger Moth. The journey began at Shoreham Airfield, taking him along the Sussex coast past Worthing Pier. As we flew out to sea, just off Marine Parade where he lived, Gerald shared a humorous and endearing detail. His wife had promised to wave her knickers in the air from their balcony as a sign of her affection. Whether she fulfilled this playful pledge remains a mystery, for I was too much of a gentleman to the last and chose not to look.

The flight was a testament to Gerald’s enduring spirit, and I am proud to have flown him that day, a final nod to the sky where he had spent some of his most defining moments. It was a fitting celebration of a century-long journey, filled with courage, humor, and an unshakable love for life and flight.

Gerald left us in 2002 having reached a glorious 102 years old. He was cremated, according to records, in the second quarter of that year. It is unknown what happened to his ashes or if any memorial has been placed to remember him by.

RIP Gerald, you are not forgotten.

Leave a reply to Jacques Girauld Cancel reply