Pilot Officer Robert Dunlop Davidson, 401 Squadron

(Royal Canadian Air Force) Service number J/88096.

Whilst driving around the district of Orne in France, I found the grave of a young Canadian Airman. He lies within the beautiful church and cemetery of Notre-Dame de Lignou, near Couterne. His resting place is in the corner of the cemetery, and is marked as a (Commonwealth War Grave) CWG.

Lignou and Couterne lie about 7 kilometres to the west of the little French house Diane and I bought in Couptrain a few years ago. I have visited his grave a few times, it is positioned in the south west corner of that very pretty Church that lies on the hill to the north of Couterne.

The year 2019 marked the 75th anniversary of this young Canadian losing his life in combat, so I decided to do a little research and thought a dedication would be appropriate. I hope you do read on as I have accumulated quite a bit on this young man that gave his life so we can live as we do today.

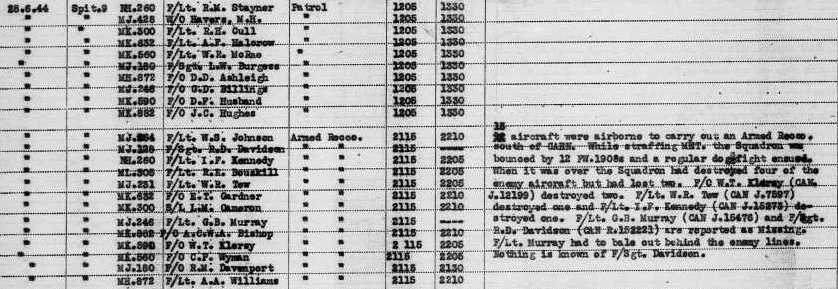

On the 28th June 1944 21 year old Pilot Officer Robert Dunlop Davidson was flying with 401 (Royal Canadian Air Force) Squadron on an armed reconnaissance mission, in his Supermarine Spitfire a Mark LFIX MJ428 (built at Castle Bromwich Aircraft Factory), when he was shot down by a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 south of Caen.

He was laid to rest at COUTERNE (LIGNOU) Churchyard by the local French community in 1944 led by a Messier Norbert Hureau from Argentan, Normandy .

Robert Dunlop Davidson, was to be known as Bob according to Lloyd Berryman, a fellow pilot from Hamilton, I have more on Lloyd later. Bob Davidson was born in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada in 1923. The son of William and Jessie Davidson of Hamilton, Ontario Canada.

I have no dates as to when Bob Davidson arrived in the UK but I have found out that he was sent to 83 GSU, (Group Support Unit) which was based at that time at Redhill. Later on 83 GSU moved to Bognor, then Thorney Island, also Westhampnet and finally Dunsfold.

Group Support Units were part of the 2nd Tactical Air Force that supplied spare pilots and aircraft to the individual squadrons within the groups and in this case Bob was allocated to 401 squadron RCAF and he joined them on the 5th June whilst they were still based at Tangmere.

It looks like Bob Davidson was given a couple of days to settle into squadron life as he was not listed for ops till the 7th June. The Operational records show him placed as no 2 to Squadron leader Cameron. This was to be his test as wing-man to the guvnor and no doubt he was told to stick to the leader like glue.

Between 7th June and the fateful 28th June he would fly 20 operational flights with 401 squadron.

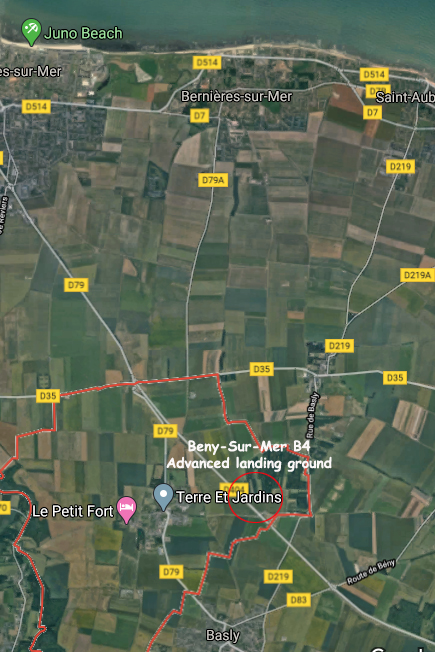

On The 18th June the squadron moved across the channel to to Beny-Sur–Mer where they would then continue to operate, mainly covering beach head patrols.

Finally on the 28th June having taken off at 21.15 he went missing during an engagement with Focke Wolf 190’s.

No one in 401 saw him go down that day he is just recorded as missing, (nothing is known) in the summary of their daily events form . Interesting though that here within that daily operations form AIR 27/1774-12 he is listed as Flight Sergeant R D Davidson R.152221. As indeed he was all the way through with 401 squadron.

Here are some notes from Lloyd Berryman who served in 412 squadron and knew Bob Davidson as they were both from Hamilton Ontario, in Canada. Lloyd was at last, in 1994 to find out what happened to his friend and visit his grave site in 2004.

Lloyd writes.

On June 27, 1944, 126 Wing of the Second Tactical Air Force was at Beny-sur-Mer where we landed a week earlier. It was the base for three squadrons of Spitfires in Normandy.

On that date I learned that Bob Davidson, a friend from my hometown of Hamilton, had been posted to 401 Squadron on our airfield. I hadn’t known Bob intimately, as we grew up in opposite areas of Hamilton, though I got to know him briefly after my family had moved to the eastern area of that city. Regardless, he was the kind of person you liked instinctively and I hustled over to 401 to extend greetings. My recollection is we spent a most enjoyable period discussing things back home and I left him with the assurance of spending more time as soon as possible.

Bob Davidson was shot down and killed in the Argentan area of Normandy not far from our home base. It came as a great shock, yet by the very nature of our involvement, it also was a frequent experience.

In 1994, some 50 years later, a request for anyone knowing of Bob Davidson, posted in our Canadian Fighter Pilots bulletin to contact a Norbert Hureau in Argentan, Normandy. Canadian Veterans were to visit that area of France in 1994 for the 50th anniversary of the D-Day landings. Mr. Hureau had a ring belonging to Bob Davidson that he would like returned to the Davidson family. I communicated immediately with Hureau who turned out to be not only a historian but was also part of the French underground in World War Two who had recovered Bob Davidson’s body and undertaken a proper internment during the war.

Upon learning of my inclusion in the 60th anniversary ceremonies in 2004, I undertook to contact Hureau again advising my impending arrival in Normandy. Much to my surprise I received a phone call several weeks later and discussed (through a translator) possibilities for meeting at our scheduled visit to the Canadian Cemetery at Bretteville, Normandy, on June 8, 2004. At long last I would be able to pay my respect at the grave site of my long lost friend from 401 Squadron. It turned out to be a most exhausting undertaking.

As arranged, Mr. Hureau awaited my arrival at Cintheau Cemetery and after opening ceremonies, we departed from Bretteville. Unfortunately, without a translator, our driving around Argentan to visit the remote areas

We ended up at Mr. Hureau’s home twice to examine an enormous amount of historical data before finally arriving at a school site to meet several other people. Finally, we arrived at the exact location where Bob Davidson was shot down in a hamlet named (Courteres)

Following a brief ceremony we progressed to his burial site in the cemetery of a small church in Lignou. It was a momentous experience for me regardless of how enduring it turned out to be.

There was however a final obligation unbeknown to me. We arrived back at the school we had started from, where a class of youngsters had been waiting over two hours to meet a friend of the Canadian pilot buried in their cemetery.

What a day, despite my arrival back in Deauville at 8 p.m. I can reflect that it was a very special for me to salute my colleague and friend Bob Davidson and to say goodbye.

Lloyd also has an interesting story about delivering beer by Spitfire utilising the jettison-able long range fuel tanks. Which I extend to this piece in dedication to Bobs friend from Hamilton Lloyd Berryman.

Lloyd Berryman began with the rank of Flying Officer and had attained Flight Lieutenant by the war’s end. He was a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force 412 Squadron, 2nd Tactical Air Force, 126 Wing. He was based in England, often at Biggin Hill airfield just south of London.

As a pilot, Lloyd Berryman engaged in the Allies’ aerial, land and sea assaults on German-occupied land in northern France and Belgium, most notably the June 6, 1944 D-Day invasion of Normandy, France.

A Flyer’s Remembrance: The Beer Run, by Lloyd Berryman

On June 13, 1944, (D-Day plus seven) number 412 (Falcon) Squadron, along with the others comprising 126 Wing gathered for a briefing by W/C Keith Hodson at our Tangmere base. We would get details of our now regular Beach Patrol activities, only this one had a slight variation.

The Wingco singled me out to arrange delivery of a sizable shipment of beer to our new airstrip being completed at Beny-sur-Mer.

The instructions went something like this – “Get a couple other pilots and arrange with the Officers Mess to steam out the jet tanks and load them up with beer. When we get over the beachhead drop out of formation and land on the strip. We’re told the Nazis are fouling the drinking water so it will be appreciated.”

“There’s no trouble finding the strip, the Battleship Rodney is firing salvoes on Caen and it’s immediately below. We’ll be flying over at 13,000 so the beer will be cold enough when you arrive.”

I remember getting Murray Haver from Hamilton and a third pilot (whose name escapes me) to carry out the caper. In reflection it now seems like an appropriate Air Force gesture for which the erks (infantrymen) would be most appreciative.

By the time I got down to 5,000 feet the welcoming from the Rodney was hardly inviting but sure enough there was the strip. Wheels down and in we go, three Spits with 90 gallon jet tanks fully loaded with cool beer. As I rolled to the end of the mesh runway it was hard to figure . . . there was absolutely no one in sight. What do we do now, I wondered, we can’t just sit here and wait for someone to show up. What’s with the communications?

Finally I saw someone peering out at us from behind a tree and I waved frantically to get him out to the aircraft. Sure enough out bounds this army type and he climbs onto the wing with the welcome . . . “What the hell are you doing here?”

Whereupon he got a short, but nevertheless terse, version of the story.

“Look,” he said “can you see that church steeple at the far end of the strip? Well it’s loaded with German snipers and we’ve been all day trying to clear them out so you better drop your tanks and bugger off before it’s too late.” In moments we were out of there but such was the welcoming for the first Spitfire at our B4 airstrip in Normandy.

The unbelievable sequel to this story took place in the early 1950s at Ford Motor Company in Windsor Ontario, where I was employed at the time. A chap arrived to discuss some business and enquired if I had been in the Air Force. “Yes, indeed,” I responded. “Did you by chance land at Beny-sur-Mer in Normandy with two other Spitfires with jet tanks loaded with beer?” he asked.

“Yes for sure I did,” I answered, “But how on earth would you possibly be aware of that?”

“Well I’ll tell you,” he said, “I was the guy who climbed on your wing and told you to bugger off.”

We finished the afternoon reminiscing.

Lloyd Berryman now has something in common with Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 2007 he received a 205-year-old honour created by — and both worn and bestowed by — that famous French military leader and emperor.

Berryman joked that as he is receiving the highest award from the French government he has been told it means soon he can be called ‘sir’ or, more appropriately, ‘monsieur’.

The Second World War fighter pilot says he is “overwhelmed” by the news he is one of 50 Canadians who will be given that country’s Legion of Honour medal.

The 85-year-old former alderman and mayor of Burlington (1966-67) said he was informed of the accolade last December but waited until he was given an actual date and location for a special ceremony before making his pride public.

On Thursday he showed the Post a formal letter he received last December from the Ambassador of France in Canada, Daniel Jouanneau. The four-paragraph note congratulates him for “… a reward you greatly deserve for the exemplary and outstanding behaviour you demonstrated during the fierce battles of the liberation of France and Europe. By awarding you such a high distinction, France wants to honour a great Canadian soldier who fought for freedom….”

The French Consul General of France in Toronto, Philippe Delacroix , told the Post that Berryman’s military record, which included flying 135 missions, “is quite extraordinary”.

Delacroix recently informed Berryman he and eight other Canadian veterans will receive the Ordre national de la Legion d’honneur (Legion of Honour) on Friday, April 27 at the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. Many original and reconstructed military aircraft are housed at the museum, including an authentic single-engine, single-seater Spitfire, the kind Berryman piloted from 1942-44.

Another longtime local resident, Ed McAndrew, 82, is also receiving the Legion of Honour the same day. An infantryman with the Regina Rifles, the Chicago-born, Hamilton-raised private landed at Juno Beach on D-Day and soon after lost part of a leg in Normandy.

Berryman is looking forward to the ceremony in Mount Hope.

“When I opened it (letter) up I had to sit down for several minutes I was so overwhelmed. I had heard of the Legion of Honour but I knew no one in my squadron had received it.”

He still recalls vividly images of destruction and human desperation in the French countryside and the towns of Belgium and Holland, as the Allies pushed the Germans back. Such memories put the Legion of Honour in perspective for him, he said.

“I have so much respect for the French people, who endured much difficulty — the people of Normandy and Caen… The same people suffered from bombings long before and after D-Day… They suffered more than the people who were supposed to liberate them.”

Berryman owns a number of service medals and ribbons for his war efforts but the most prestigious one he received prior to the Legion of Honour was the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

The circumstances of how he was supposed to receive the DFC and when he actually did is a story he rarely tells due to some measure of embarrassment.

He said he was notified by letter he was to go to Buckingham Palace to meet King George VI (the Queen’s father) and receive the DFC for shooting down three enemy aircraft in one day in 1944 while providing air cover for Allied forces at river bridges in Nijmegen in Holland.

At the time he got the Royal request for his presence, in November 1944, he had a conflicting date to return home to Canada by sea, and he was determined not to miss the boat, so to speak. He skipped the Royal treatment. His parents in Hamilton received his DFC medal by mail several weeks later.

It’s hard for Berryman to compare the magnitude of the DFC to the Legion of Honour.

“It’s a (military) rule that any foreign medals are noted (but) you put your own country’s ahead. It’s (Legion of Honour) the top honour of France; the top honour in Canada is the Victoria Cross and then the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

“The Legion of Honour supercedes the Distinguished Service Order. In my own viewpoint, it (Legion) exceeds the Distinguished Flying Cross. It’s at a level all its own.”

Nowadays Berryman spends part of his retirement speaking about his war experiences to high school students. He estimates he has talked to about 6,000 in the last five years

The passing of LLoyd Berryman.

Lloyd Berryman trained to become a fighter pilot at the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) station in Alymer, Ont. He was commissioned in 1943 and flew more than 200 sorties before returning to Canada in November 1944. – Special to Burlington Post

Lloyd Berryman, former mayor of Burlington, has died. He was 90

Born on the last day of 1921 in Hamilton, Mr. Berryman made Burlington his home after 1950. He served as a town councillor from 1964-65 and was the mayor from 1966-67.

His actions in the Second World War earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross and, in recent years, the prestigious Legion D’Honneur from France.

31st December 1921 – Apr 26, 2012

Rest in peace Sir:

Leave a comment